When a bank run occurred in the Great Depression, Roosevelt simply declared a banking “holiday” which was to close banks for a time:

“After a month-long run on American banks, Franklin Delano Roosevelt proclaimed a Bank Holiday, beginning March 6, 1933, that shut down the banking system. When the banks reopened on March 13, depositors stood in line to return their hoarded cash. This article attributes the success of the Bank Holiday and the remarkable turnaround in the public’s confidence to the Emergency Banking Act, passed by Congress on March 9, 1933. Roosevelt used the emergency currency provisions of the Act to encourage the Federal Reserve to create de facto 100 percent deposit insurance in the reopened banks. The contemporary press confirms that the public recognized the implicit guarantee and, as a result, believed that the reopened banks would be safe, as the President explained in his first Fireside Chat on March 12, 1933. Americans responded by returning more than half of their hoarded cash to the banks within two weeks and by bidding up stock prices by the largest ever one-day percentage price increase on March 15—the first trading day after the Bank Holiday ended.”

Federal Reserve of New York

So, over time the Fed created their FDIC deposit insurance program to attempt to limit future risk. The problem is this likely creates an equally large change in perception of risk by the public, who implicitly believe they are safe. This is true to a degree, like more insurances (e.g. home, auto), but when the insurance keeps taking on more risk, as it has in the last two decades, the problems becomes systemic, it moral hazard increases; or perhaps, it’s the other way around: Moral hazard leads to systemic risk. Either way, the more safe something seems, the more people trust it and act in a way that demonstrates that trust, even though safety is always an illusion, especially in financial markets.

Even the Washignton Post recently contributed to the popular feeling when discussing Credit Suisse: “Thankfully, these aren’t your grandad’s bank runs – or even your aunt’s. They are much more benign than the Panic of 1857, for example, when, according to one account, “Wall Street literally was filled with depositors hurrying to withdraw their funds.” Banks in New York City lost about half their deposits in that episode. A series of cascading bank runs 75 years later contributed to the Great Depression and the failure of about 9,000 institutions. In contrast, this year’s events aren’t really bank runs at all.”

That’s exactly due to the process I describe above. Individual safety moves to a collective safety (e.g. govt level), but then eventually that gives way as nations rise and fall.

Now if you do not know what a bank run is, start here: Bank Run: Definition, How It Works, History, Examples and Effects (investopedia.com)

Have There Been Any Recent Bank Runs?

Part of the reason I wrote this was due to Credit Suisse’s bank run in Nov of 2022, which seems to have stopped for now. “Credit Suisse Estimates $1.6B Loss After $88.3B Withdrawn in Bank Run”

“During the financial crisis of 2008, there were instances of runs on individual banks, such as IndyMac Bank in California and Washington Mutual in Seattle, but these were relatively isolated incidents. The crisis was primarily caused by problems in the mortgage and housing markets, which led to a widespread loss of confidence in the financial system and a decline in the value of financial assets. This, in turn, led to a credit crunch, as financial institutions became more hesitant to lend money and investors became more hesitant to buy financial assets. The crisis was eventually resolved through a combination of government intervention, including bailouts and guarantees for certain types of financial assets, and the restructuring of troubled financial institutions.”

And seems Chase/Wells Fargo barely got the Wachovia deal done:

Wachovia was a large regional bank with operations in the eastern United States that was hit hard by the crisis. In September 2008, the bank agreed to be acquired by Wells Fargo in a deal that was initially valued at $15.1 billion. However, later that month, the Federal Reserve approved a merger between Wachovia and Citigroup, which valued Wachovia at $2.2 billion. This led to a legal battle between Wells Fargo and Citigroup over the acquisition of Wachovia, which was eventually resolved in favor of Wells Fargo.

Source: https://chat.openai.com/ *

The acquisition of Wachovia by Wells Fargo raised concerns about competition and the concentration of financial power in the hands of a few large banks. It also led to some criticism over the role of the Federal Reserve in the acquisition process, with some people arguing that the Fed had acted in favor of Citigroup.

Despite these challenges and controversies, the acquisition of Wachovia by Wells Fargo was ultimately completed and helped to strengthen Wells Fargo’s position as a major player in the banking industry.

Could Bank Runs Exist in the Future?

Some have suggested recently that crypto, Blackrock (the largest investment fund in the world), and others are experience patterns that may lead to a run, even though they are not technically not a bank run, collectively, actions like these can lead to market panics, collapses, and runs on banks. What is most important to realize is the idea of contagion in markets with lots of credit. Credit is a multiplier of money in a positive direction when investments are working, but also a multiplier of money downward when systems contract.

Not sure how banks could actually stop a bank run in the future other than by force (govt intervention) like they did in the Depression. In other countries, limiting what people can withdraw in a day became a real phenomenon (e.g. Cyprus), so I do expect that at some point, that risk of preservation by govt will override individual citizens rights.

Even Britain’s credit has been recently compared to some of the worst debt cases like Greece. No matter how advanced, intelligent, sophisticated, or organized a civilization may be, it will always have problems at different points in time, especially economic issues.

Do the Bank Runs in 2008 Prove the FDIC System Works?

What is interesting is to see the real stress tests that occurred in 2008. The Fed’s website explains how the Wachovia deal in ’08 barely panned out, so the full faith and trust of the US govt is clearly a function of the present.

You can be sure people underestimate future financial risk, believing that somehow new rules/regulations/restrictions of the past will guarantee safety. In fact, there is a belief that “banks are far more secure today than in 2008” because regulation forced them to act less risky in certain lending aspects, which is why it’s more difficult to borrow money to buy a home; however new risks will always pop up in new and unexpected places. Today its crypto, private lending, Financial risks grow in shadowy corner of markets, worrying Washington – The Washington Post (googleusercontent.com)

There were a number of challenges and controversies associated with the acquisition of Wachovia by Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase after the financial crisis of 2008.

Wachovia was a large regional bank with operations in the eastern United States that was hit hard by the crisis. In September 2008, the bank agreed to be acquired by Wells Fargo in a deal that was initially valued at $15.1 billion. However, later that month, the Federal Reserve approved a merger between Wachovia and Citigroup, which valued Wachovia at $2.2 billion. This led to a legal battle between Wells Fargo and Citigroup over the acquisition of Wachovia, which was eventually resolved in favor of Wells Fargo.

The acquisition of Wachovia by Wells Fargo raised concerns about competition and the concentration of financial power in the hands of a few large banks. It also led to some criticism over the role of the Federal Reserve in the acquisition process, with some people arguing that the Fed had acted in favor of Citigroup.

Despite these challenges and controversies, the acquisition of Wachovia by Wells Fargo was ultimately completed and helped to strengthen Wells Fargo’s position as a major player in the banking industry.

Source: ChatGPT

What Condition Are FDIC Funds in Today?

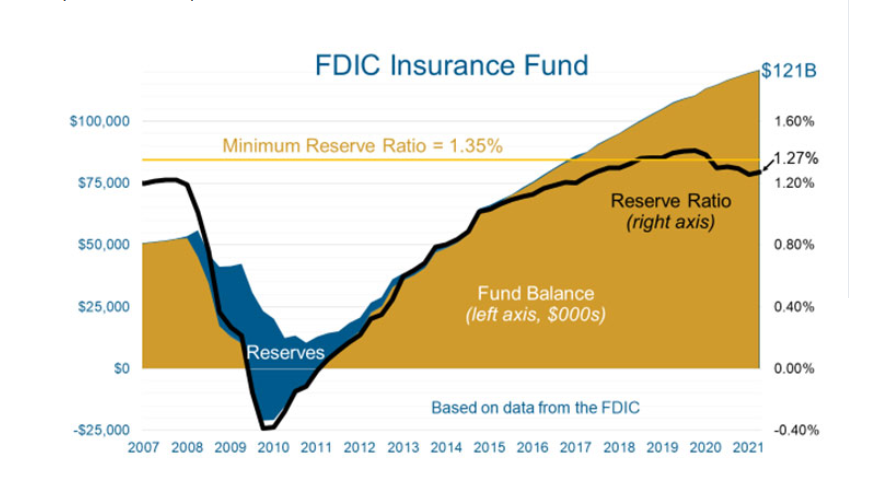

The American Bankers Association (aba.com) provides a clear view into today’s status. First off, banks pay into the FDIC insurance policy. However, not is it only underfunded since 2015, but there is perhaps a larger issue: Is there actually enough to cover a series of large bank runs? According to the same source “The FDIC Deposit Insurance Fund balance reached a record $121 billion in June 2021.” and with total bank deposits that same year at just under 20 trillion, that represents a drop in the bucket if things are to go wrong.

For example, “the most costly failure to the FDIC’s insurance fund was the June 2008 failure of IndyMac, which cost the fund $12 billion.” (Yahoo). You can see in the same chart that the fund even went negative for awhile.

My basic, elementary school math says if they need to have a mere 1% of reserves set aside for FDIC insurance, then that is probably going to be way too short for the next crisis considering the destructive potential energy building up for the last two decades by Fed, market-propping policies. If just 2% of banks failed, or even just one large bank, they would run out of money. The follow up would be clear though: more government controls over our individual lives. Did you know that 55% of people in Argentina already work for their govt? We are on the same path if you werent aware since govt spending continues to grow as a percentage of GDP.

The bigger the delays in market corrections, the harder they fall, or in the words of Fed critic Terry Burnham “The trouble with trying to make the world safe for stupidity is that it creates fragility.” Sure, it’s difficult to say where the Fed should have drawn the line, but it seems like every time a crisis goes by, they are just as afraid to let nature take its course, so the momentum builds.

This behavior of the FDIC to insurance deposits leads to problems in group thinking, herd behavior, as described in the social sciences. Every time I ask the question “is my money safe in your bank” the response is undeniably the same “Of course it is, its insured” as if insurance companies never fail (let’s ignore AIG,

Are There Banks That Store Cash, But Do Not Lend Out?

No, and Googling “how to start my own bank” reveals the cost of starting your own bank is astronomical due to regulation requirements, but I guess a safe is the equivalent of a personal bank.

PBS reports that history shows this very thing has indeed happened before:

“there was a famous anti-lending bank and it was also a “BofA” — the Bank of Amsterdam, founded in 1609. The Dutch BofA charged customers for safe-keeping, did not make loans and did not allow depositors to get their money out immediately. Adam Smith discusses this BofA favorably in his “Wealth of Nations,” published in 1776. Unfortunately — and unbeknownst to Smith — the Bank of Amsterdam had starting secretly making risky loans to ventures in the East Indies and other areas, just like any other bank. When these risky ventures failed, so did the BofA.)”

PBS.org

Alternatives to Storing Cash in Banks: Safes?

What about hiding cash under mattresses? South Americans, and esp. places like Argentina, show that keeping valuables at home make you a target for home invasion robberies. The risk of robbery in some countries like Costa Rica are now about 1 in 50 people per year; about 30 times higher than here in the U.S. Recall that in South America, and places like Peru, people really do trust their mattress more than banks, probably because the “obvious” type of corruption is higher there. Here we may have more corruption, but it’s more sophisticated and subtle, like when the govt uses opaque and obscuring words like “quantitative easing” to hide the fact they are really just printing money, giving bailouts, and other “stimulus” to “ease” the downward momentum of markets/economies.

I figure there will be a moment to switch from cash by buying other investments, but most other asset classes seem very expensive right now compared to historical norms. Gold and other metals are very volatile in price and just as dangerous to keep at home.

The Moral Hazard of Collective Group Behavior

An observation I made and tracked for some time is this: The more you try to guarantee a population’s collective survival, the more you ensure its collective demise. This is why communism and other methods to protect entire societies ultimate fail. They are anti-evolutionary for a society, but the typical end of many I presume. This is why for example, the mass bailout of banks was seen as a temporary way to alleviate banks of their personal accountability, but was likely to allow them to continue into the future, knowing that they will always be bailed out. It occurs when personal accountability decreases and people do not pay for their poor behavior, whether punishments or natural means such as financial losses.

“For example, if a financial institution knows that its deposits are insured by the government up to a certain amount, it may be more inclined to engage in risky behavior, such as making risky loans, because it knows that it will not suffer the full consequences of those risks. Similarly, if individuals know that their deposits are insured, they may be less likely to carefully monitor the financial health of their bank or to diversify their investments, since they know that their deposits are protected.”

Source: ChatGTP*

In fact, China is in many ways more free market, willing to let bad businesses suffer more than our govt has in the last two decades, which supports my underlying belief that they are becoming more free and moving upward, while we are moving in the opposite direction…for now. Let’s hope things revert.

Where the Real Focus Should Be

If there’s anything people should study, it’s the patterns of human behavior in history (unfortunately schools do not teach these). As for solutions to the current situation there are three main cures: More people (immigration/fertility, both of which are declining rapidly in the last decades); greater freedom (which both lubricates economies and is a magnet for immigration); and more work output per person (which rarely comes in times of plenty like today); and most of all, greater general morality ranging from honesty, to kindness, to support of one’s community and nation.

Now, it’s best to continue the growing moral hazard of the Fed on another piece entirely.

In summary, your savings are only as safe as people believe it is, and the system can be maintained.